29.01.2025

Failure in a production machine: Analysis and source localization

Even the best designed production machines can experience failures. A failure is a situation in which a machine cannot operate properly. The most common causes of failure include problems related to the service life of the components used, excessive use, and human error at the operating or design stage. Often, the task of an automation engineer is to diagnose the failure and eliminate its cause.

In extensive automation systems, even the simplest failure may be difficult to diagnose due to the complexity of the entire control system. An important element of the entire process is the ability to divide the problem into smaller, easier to diagnose fragments. An example of a seemingly very simple failure concerning a presented or damaged reed switch sensor detecting the end position of the actuator may turn out to be a time-consuming problem. Especially when the descriptions on the HMI operator panel display imprecise messages or they are missing. The scale of difficulty also increases when it is a machine that we are operating for the first time. Modern tools such as maintenance management systems (CMMS) play a key role in optimizing diagnostic and repair processes, enabling effective tracking of failure history, spare parts management and planning of preventive inspections.

Table of Contents

Problem identification

Let’s analyze an example failure. A production machine that produces a specific product operates in automatic mode. After starting the cycle, the machine reports a message on the HMI operator panel: the extended position of the 7A1 piece lock actuator has not been reached . The automatic process stops. Confirming the error with the Clear error button does not change the status. An example of the process of analyzing and diagnosing the situation is presented below.

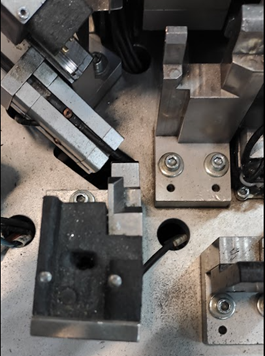

First, locate the diagnosed pneumatic actuator on the production machine. In the case of a small machine, this is a very easy task. In the case of large machines, the situation becomes complicated. Especially when the machines do not have appropriate element identification. After locating the element, you can assess the visual condition of the actuator that interests you. In our case, identification was simple due to the small number of actuators on the machine (Fig. 1). At first, no signs of damage were found.

Fig. 1. Pneumatic actuator on a production machine

Testing in manual mode

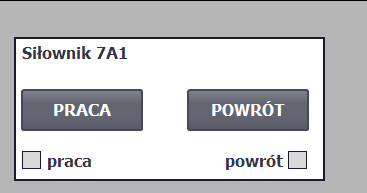

In order to verify the correct operation of the device, we switch to manual mode using the work selection switch designed for this purpose. In a properly programmed production machine, it should be possible to move each executive element separately. In our case, this is a simple manual work screen with the option of manual control WORK and RETURN and signaling the position of the actuator’s piston rod using signal lamps (Fig. 2). A standard step is to try to change the position several times. Our pneumatic actuator responds to the return button, which we can see on the HMI operator panel by lighting up the lamp and by moving the actuator. Triggering the movement in the other direction with the work button does not cause the actuator to move and the lamp to change on the screen.

Fig. 2. Manual control of the actuator with signaling

An experienced automation engineer as well as a maintenance technician first connects a similar situation with incorrectly set reed sensors signaling the actuator position. In our case, after controlling the movement in the return direction, the actuator is in the base position and on the HMI screen this state is signaled by the return lamp. The problem is the lack of working movement of the actuator.

Pneumatic diagram analysis

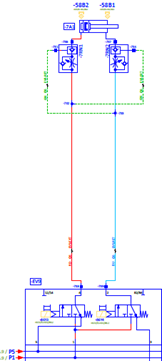

At this point, for further analysis, we move on to the pneumatic and electrical diagram of the machine. First, we analyze the pneumatic connection of the actuator. According to the fragment below (Fig. 3), the actuator 7A1 is connected to the valve EV9 .

Fig. 3. Connecting the pneumatic actuator

In practice, this is a valve position on a pneumatic island containing two 3/2 normally closed valves, controlled by an electric coil and a manual button. The valve returns to its initial state using a spring. Analyzing the actuator connection, we know that the return movement (actuator retraction) works correctly (blue line), while the problem is the actuator extension movement (red line). Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish whether the problem is on the pneumatic or electrical side. In our case, we used manual control directly on the EV9 pneumatic valve . Direct control brought the expected effect. The actuator extended. This finally confirms that the pneumatic part is working correctly.

Electrical diagram analysis

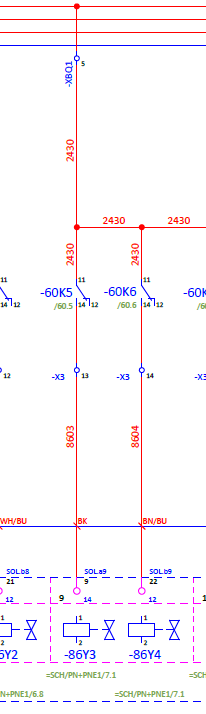

In the next step, we move on to analyzing the electrical diagram. From the pneumatic diagram, we read that the retraction movement is controlled by the solenoid valve coil number 86Y4 . After finding the coil in the electrical diagram, we move on to analyzing the fragment of the diagram that interests us (Fig. 4). The coil is powered from the potential of 2430 through the normally open contact of the 60K6 intermediate relay . In this case, there are two possibilities. No power supply on the XBQ1 strip or the 60K6 relay is not activated .

Fig.4. Electrical diagram – solenoid valve coil control

(It is worth noting here how the appropriate action very quickly reduced the possibility of failure to 2 locations.) Further analysis shows that the XBQ strip is powered directly from the machine’s safety control system. Using a multimeter, we check whether contact number 11 on the 60K6 relay is powered. The multimeter indicates a voltage of 24V DC. This means that the voltage reaches the relay, but the circuit is not closed and there is no power supply to the solenoid valve coil.

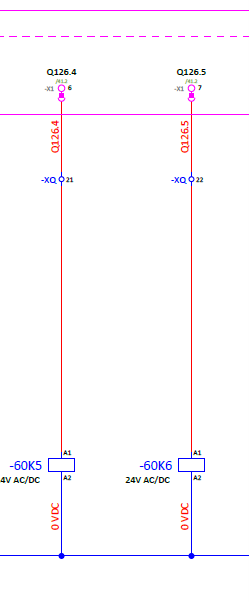

In this case, we go to the side of the electrical diagram responsible for controlling the 60K6 relay . We can see it in the fragment of the diagram below (Fig. 5.) The relays are powered directly from the PLC outputs, and the relay of interest to us from the Q126.5 digital output. At this point, the path to solving the problem again splits into 2 possible variants: a damaged relay or a non-controlled signal from the PLC . In order to verify the problem, we can check the voltage at terminals A1 and A2 of the relay or check whether the diode corresponding to our output on the PLC is lit, signaling a high state. In our case, the diode is not lit and the output is not activated. Unfortunately, further analysis of the problem is not possible without analysis in terms of the PLC program .

Fig. 5. Electrical diagram – relay control

PLC program analysis

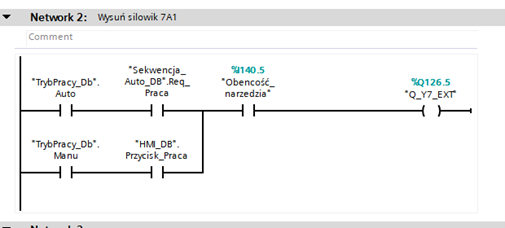

Depending on the complexity of the machine, the standard in which the program is written and the programmer’s experience, this task can be very simple or very difficult and time-consuming. The TIA Portal engineering software was used for diagnostics. In our case, we start the analysis by finding the physical address associated with our solenoid valve ( Q126.5 ). Then, using the Cross-Reference tool, we look for the place where our physical output is controlled in the program. We come to segment 2. (Fig. 6.)

Fig. 6. Program PLC

Simple logic indicates the output operation in automatic mode when the appropriate forcing from the automatic sequence occurs and in manual mode when the work button on the HMI operator panel is pressed. Where is our problem? The normally open contact of the I140.5 sensor described as the presence of a tool is connected in series with this condition. During the attempt to control the actuator, the additional sensor signaling the presence of a production tool is in a low state. This allows the power supply of the Q126.5 coil and the control of the digital output.

Solution to the problem

After cleaning and resetting the sensor, the machine returned to normal operation, both in manual and automatic mode. In our case, the problem turned out to be a dirty optical sensor, not directly related to the actuator. Due to the lack of an appropriate message on the HMI operator panel, the error masking phenomenon occurred. The message indicated a problem with the pneumatic actuator, and the problem turned out to be the optical sensor. In order to avoid a similar problem in the future, an additional alarm had to be added, which would appear when there was a request to control the actuator and the sensor remained in a low state.

Summary

Based on the situation described above, even seemingly very simple situations can cause an unexpected stoppage of a production machine. In practice, it is impossible to determine one correct algorithm for action in the event of a failure. Each situation requires an individual analysis and a different approach. In each case, however, it is worth trying to divide the problem into smaller fragments and exclude individual possibilities in the simplest way possible.

In many cases, failures are also caused by damaged or worn automation components. In order to minimize failures caused by worn components, predictive maintenance and maintenance management systems (CMMS) are used. A system such as CMMS allows for preventive maintenance, reporting faults and maintenance planning. CMMS systems also allow for parts inventory management, which is crucial in the case of tight production schedules.

To sum up the described failure, in many situations it is difficult to avoid production downtime resulting from human errors at the design stage. However, it is easy to minimize errors resulting from suboptimal and unorganized maintenance using dedicated systems.